The blue wave

The blueberry industry has grown at an astonishing rate for years in terms of prices, consumer demand and acreage.

So what could go wrong?

Plenty, cautions industry consultant John Shelford. He described the industry’s growth as the Blue Wave and posed the question, will growers continue to ride it or crash? His advice: Manage risks.

Shelford spoke in January at the Washington Highbush Blueberry Workshop, organized by Washington State University Extension. The workshop covered advances in horticultural management and the future of production.

Shelford has worked in the blueberry business for 40 years. He is a Florida-based industry consultant who served as president of Naturipe Farms LLC and as president of Hortifrut NA Inc. He has seen astonishing change during his career.

Blueberries were a regional crop and little known nationally before 1986, he said. Today, consumer demand is strong, benefiting from research showing the health effects of blueberries.

Ninety-nine percent of households believe blueberries are a healthy food, he said.

Statistics on blueberries are tracked by region and by highbush (historically described as “cultivated”) versus “wild” blueberries.

Highbush blueberries grow from planted bushes. “Wild” arise from areas where competing plants may have been cleared, allowing natural propagation of bushes primarily through underground runners.

Wild blueberries are not necessarily “wild” as similar horticultural practices are essential, including herbicides and pesticides. Wild blueberries are often irrigated and pruned as well.

Here’s how the categories are explained by Lisa Wasko DeVetter, a workshop organizer and WSU Assistant Professor of Small Fruit Horticulture based in Mount Vernon, Washington:

“‘Highbush’ is a way we differentiate among other blueberry species that are cultivated,” she said. “We have low-growing ‘lowbush’ blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium, also known as “wild blueberry”) grown in the Maine area. Then we have ‘highbush’ (mostly Vaccinium corymbosum). Within highbush, we have low- and high-chill types that are commonly referred to as southern and northern highbush, respectively. Then we have rabbiteye blueberry (Vaccinium ashei). On top of that, we have crosses of low and highbush types called ‘half-high’ blueberry.”

In Washington, the dominant species is the highbush.

Statics kept by Shelford show how highbush blueberry production has grown and shifted to the Northwest.

In 1996, total production nationally was 164 million pounds, with the largest producer being the Great Lakes at 45 million pounds, versus 25 million pounds from Oregon and Washington.

Last year, total production was 711 million pounds, with 75 million pounds from the Great Lakes versus 196 million pounds from Oregon and Washington.

If you count British Columbia and California, the shift from the East to the West is even more dramatic during that period, from 38 percent to 59 percent of total production.

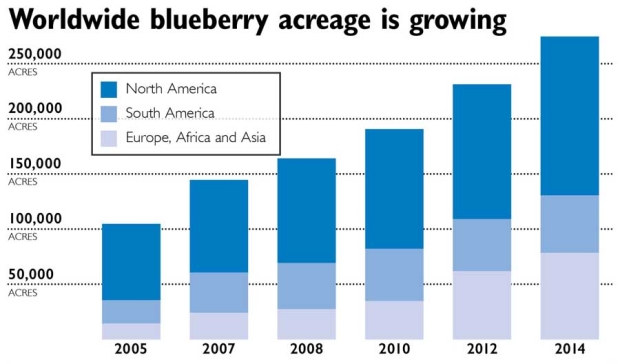

Blueberry plantings continue at a brisk pace. Between 2007 and 2014, worldwide plantings grew at a compounded annual rate of 10 percent.

In North America, the figure for that period was 8 percent. By the end of 2014, blueberry acreage in North America totaled 143,636 acres. Worldwide, the total was 273,929 acres.

Shelford sees no slowdown in plantings, thus the basis for his cautions. He sees a number of competitive threats to blueberry growers.

For starters, said Shelford, the industry itself is parting ways. Wild blueberries are no longer an “aligned competitor” with highbush blueberries. They are now a direct competitor.

Wild blueberry growers now differentiate their product as “the better blueberry.” Wild blueberries taste better and provide twice the amount of antioxidants of planted blueberries, says the trade group Wild Blueberries of North America.

Second, Shelford said population growth is slowing in the United States, the industry’s most important market.

As a third dynamic, Shelford said blueberries as a consumer choice grow or hold market share at the expense of some other food choice, such as apples; he calls that “share of stomach.”

Shelford sees big change. Thus far, consumer demand and prices were strong, so much so that growers could expect profitability.

Those days are ending, in Shelford’s view. He sees pressures on profitability for U.S. blueberry growers.

He expects a softening in demand, greater competition from imported fruit, higher production costs and stagnation in prices, making it harder for higher-cost producers to make a profit.

He’s watching to see if the blueberry market goes the way of the apple market, in which proprietary varieties fetch higher prices at the supermarket. In the United Kingdom, blueberries can be found packaged with labels stating the blueberry variety.

Shelford sees added regulatory costs coming from the Food Safety Modernization Act that will especially disadvantage smaller producers.

Regulations are far stricter on frozen berries than fresh berries, for example requiring testing for Escherichia coli 0157:H7 (E. coli), Listeria monocytogenes (listeria), salmonella and other pathogens.

And yet, Shelford wonders when a kill-step will be required for fresh blueberries as a means of eradicating pathogens.

On the positive side, Shelford said the message that blueberries are healthy continues to drive sales. More than half of Americans have seen news stories about the health benefits of blueberries.

Consumers today are twice as likely as they were nine years ago to buy blueberries in the coming year, said Shelford. Fresh blueberries have moved up in consumer preference over other berries.

In rankings with strawberries, blackberries, boysenberries, raspberries and cranberries, Shelford reported, blueberries have replaced strawberries as consumers’ first choice.

Shelford challenges growers to strengthen their businesses by taking a number of steps, such as dedication to cost containment, food safety, strong marketing and a focus on quality.

Those are key to winning “the share of the stomach.”

02/22/2016

– by O. Casey Corr

Good Fruit Grower