Industry Chronicles: The Arrival of Blueberries in South America

Blueberries have a rich historical legacy that transcends time. They were once a cornerstone in the diets of hunter-gatherer tribes, a culinary treasure for the pilgrims arriving in Plymouth, MA, in 1620, introduced to them by the Wampanoag people. Their origin remains uncertain, with some attributing it to North America and others to Northern Europe, Northern Africa and Asia. What is certain, however, is that they underwent a transformative shift from being wild fruit to becoming cultivated for commercial purposes just over a century ago.

“This is one of the more recently domesticated fruit species, as this transformation occurred in the early 20th century. In 1911, in the state of New Jersey, the first variety intended for planting by farmers was developed,” explains agronomist Carlos Muñoz Schick, who holds a PhD from the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences at the University of Chile and worked with the initial blueberry plants that arrived in Chile at the Agricultural Research Institute (INIA).

Blueberries, in fact, aren’t a single species but a group of them, all belonging to the Vaccinium genus within the Ericaceae family. But one species stands out on the global stage: Vaccinium corymbosum, better known as the Highbush blueberry in the English-speaking world. Currently, it thrives across almost 250,000 hectares (618,000 acres), producing approximately two million tons of blueberries.

These small blue orbs are quite particular about their growing conditions, which initially limited their production to a select few countries. Nonetheless, as time passed and traditional barriers were broken down, more nations embraced blueberry production.

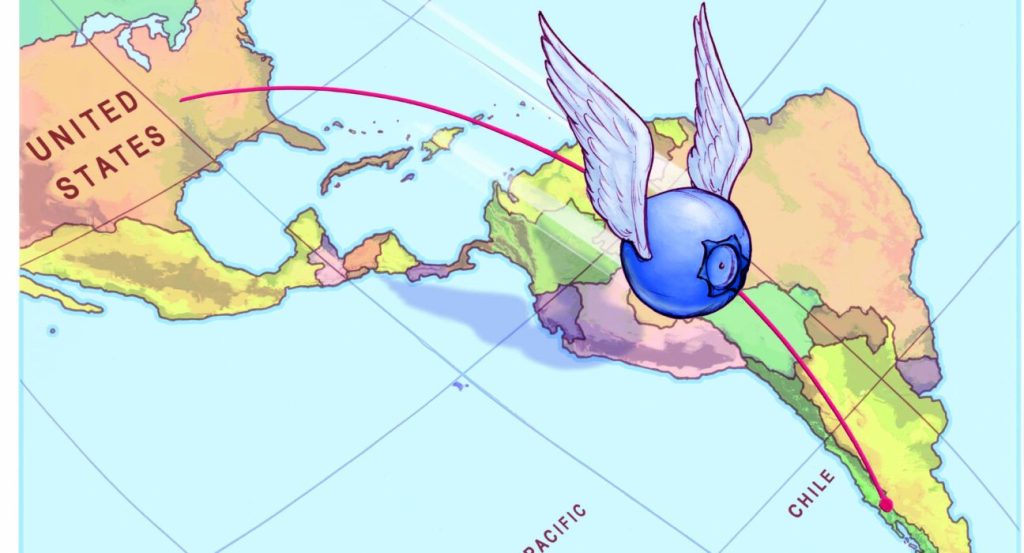

While blueberries have enjoyed a long history of popularity in the United States and Canada, they had remained relatively unknown in South America. Their introduction to the region occurred in stages, with Chile taking the lead, followed by Argentina. As the foundations of the industry grew stronger, Peru entered the arena and swiftly established itself as a major player.

Chile’s southern region was selected as the ideal location for the introduction of blueberries to the country, marking the inception of formal blueberry cultivation in South America. The plants have a preference for acidic soils with low calcium content; they are classified as acidophilic and calcifuge.

“This led us to evaluate them at the experimental stations in southern Chile, where trumao soils are predominant. These soils, derived from volcanic ashes, exhibit acidic pH levels, minimal calcium content, and relatively high porosity,” explains Muñoz.

In October 1979, the initial blueberry varieties arrived, all belonging to the V. corymbosum species: Berkeley, Coville, Earlyblue, Herbert and Jersey. By December 1982, the selection expanded to include Atlantic, Bluecrop, Bluerey, Concord, Rancocas, Stanley, Bluejay, Bluetta, Collins, Elliott, Northland and Patriot.

“Subsequently, in December 1985, we made the decision to import varieties of the so-called Rabbiteye blueberry, which falls under the V. ashei species. Sixteen varieties were introduced, many of which continue to be cultivated today, such as Brightwell, Centurion, Tifblue and Woodard. These blueberries are known for their higher productivity and superior postharvest characteristics, although their fruit quality falls short of the Highbush variety,” says Muñoz.

During the same period, Chile’s Austral University conducted trials on a similar scale, focusing on minor fruits and launching a blueberry introduction and evaluation program primarily centered on Highbush varieties.

In an era marked by the economic crisis of the 1980s, numerous dairy, livestock and agricultural companies faced bankruptcy in the then Los Lagos Region in southern Chile. Berries emerged as a promising avenue for economic activity, and blueberries were among the crops singled out for development.

“The Chile Foundation, established in 1976 through an agreement between the Chilean government and ITT Corporation [an American worldwide manufacturing company based in Stamford, CT], aimed to create a project that prioritized labor-intensive crops suitable for export, with the dual goals of job creation and foreign currency generation,” explains José Plutarco Dinamarca, an agronomist who led Berries La Unión, the first company to commercially produce blueberries in South America.

To bring this project to fruition, prominent families and entrepreneurs from the southern region collaborated on a partnership that supplied the necessary capital. A field in the town of Choroico, La Unión, served as the backdrop for the cultivation, encompassing approximately 50 hectares (124 acres) of modern raspberry varieties, red and black currants, hybrid blackberries, gooseberries and an additional 10 hectares (25 acres) dedicated to blueberries.

“This marked the inception of the first company in the south to produce, process and export berries, and for most species and varieties, it was a pioneering endeavor in Chile. It played a pivotal role in training many professionals, technicians and specialized workers in these crops, who were previously scarce in the country. It also created major employment opportunities for women, who had fewer job alternatives until then,” recounts Dinamarca.

“We selected a couple of early-production varieties, two mid-season varieties and finally, two late-season varieties with the aim of commencing the harvest in La Unión, located 450 miles (750 kilometers) south of Santiago, around mid-December, and ideally concluding it by the end of March or mid-April. Our goal was to maximize the production timeline, but back then, as the pioneers of blueberry production in Chile, we were uncertain about when prices would peak,” says Dinamarca.

The blueberry plants embarked on their journey in two 20-foot shipping containers equipped with temperature control, reaching their new home a month later. While in the United States, these plants were in a dormant state, and the plan was to unload them in San Antonio — a major port in Chile’s central Valparaiso Region — then transport them to a nearby cold storage facility (since such facilities were scarce in the south), and store them there until planting in May or June. “This strategy exposed the plants to two consecutive winters, and then, during the Chilean spring, they began to sprout, transitioning from American plants to Chilean ones,” explains Dinamarca.

From South Haven, MI, their route took them through the Panama Canal, located near the equator. It was crucial to maintain the temperature inside the containers to prevent the plants from sprouting during the journey. Upon arrival at the port of San Antonio and after reviewing the temperature charts, they discovered that one of the containers had reached 20°C (68°F).

When inspectors from Chile’s Agricultural and Livestock Service (SAG) opened the container, they found that “the plants had not developed swollen buds, but rather that Penicillium, a cosmopolitan fungus, had appeared. Consequently, they made the difficult decision to destroy the entire batch by fire,” says Dinamarca. “I have cried very few times in my life, and witnessing the burning of the plants was one of those moments. It posed a threat to a project that was of great importance to the country and all the hard work we had invested in it. What saddened me the most was the lack of understanding from the experts.”

Having received the insurance money, he revisited the U.S. nursery for more plants. This time, he flew back, reducing risks. Entry was smooth, and they moved the plants to Choroico. There, they replicated the U.S. planting method, cultivating 10 hectares with six varieties.

Trial and Error

Rudy Quezada, an agricultural technician at Berries La Unión and currently the administrator of Agropecuaria Unihue — another agricultural company — explains, “In a second phase, in 1987, plants from the United States and New Zealand arrived, and they underwent the quarantine period in the field. Following that, Berries La Unión established a nursery, initiated plant multiplication, and began laying the foundation for the first blueberry fields here in the south.”

A professional technical team was also assembled to offer guidance for these new crops in an area with no prior experience in fruit cultivation. “The primary focus for the Chile Foundation was replication, which meant encouraging other producers to get involved in cultivation. That’s why we started producing plants, as everyone was eager to join in. We performed exceptionally well. Since we were the pioneers in fresh blueberry production in Chile, we had a significant advantage in the industry,” says Dinamarca.

Following the eventful initial phase, blueberry cultivation took root in the southern region. Agrícola Ñancul emerged as one of the pioneering local companies to embrace blueberries. Their journey began with a 50-hectare (124-acre) field located just three miles (five kilometers) from La Unión, according to Luis Alberto Sáenz, who served as their manager until a year and a half ago.

The early days were far from smooth. “We encountered a multitude of challenges. First, there was the task of identifying the optimal locations for crop development. Labor availability was another concern; although there was a workforce, training was essential. Then, there was the complex issue of managing agrochemicals, coupled with the challenge of sourcing high-quality planting material. With limited research available, we often found ourselves planting varieties that didn’t yield the desired results,” notes Sáenz.

This period was marked by trial and error, a journey of discovery as they adapted to the demands of blueberry cultivation. Sáenz vividly recalls that during this era, there were technical recommendations that seemed quite absurd, such as “planting six rows of one variety, followed by six rows of another, all intermixed, under the belief that rigorous cross-pollination was required.” This notion has subsequently been debunked.

Read the full article here!

*This publication is original from Vision Magazine US