Opinion: What’s in store for Chile’s U.S.-bound blueberry trade?

By Agronometrics CEO Colin Fain

The last season for Chilean blueberry exports to the U.S. gives us cause for reflection. In this article we will explore what the hard data from the market say, and how movements in the 2015-16 season add to a rich story that can shed light on the category’s future.

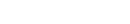

Starting with a basic analysis of the Chilean season, data given by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) indicate the market received 56,700MT, representing a year-on-year increase of 0.6%. An unexpectedly cold and rainy spring led to a delay in exported volume, complemented by more weather-related problems at the end of the deal caused by El Niño. The result was a concentration of volume in the first eight weeks of 2016, accounting for 71% of Chile’s exported volume.

In general, the reaction of pricing for Chilean blueberries was in line with what was seen in previous years; prices were higher at the beginning and end of the season, but still lower year-on-year. This could be explained by an increase in volumes from origins that compete with Chile, such as Argentina, Peru and Mexico, which meant total imports from week 40 of 2015 to week 14 of 2016 grew 7% to 78,800MT. However, from week 1 to 5 is when Chile had less competition and prices increased year-on-year, indicating higher market demand as volumes were also higher.

Historical context

A post-mortem at the end of a season often serves to reaffirm what everyone already knows. But as an analyst I see my job as utilizing scientific methodologies to get intelligence and information that is not so obvious, to provide objective knowledge that can complement the day-to-day activities and decision-making of growers and buyers in the industry.

Blueberries are by far one of the most interesting crops in fresh produce. With constant growth over the last 10 years they’ve offered a very attractive business, growing from 67,000 metric tons (MT) in 2005 to 218,000MT in 2015. It’s generated great fortunes for some, combined with huge failures for other companies that have been the victims of the insatiable battle between supply and demand. To give you some context about these movements, let’s get deeper with the numbers in a way never before done in the industry.

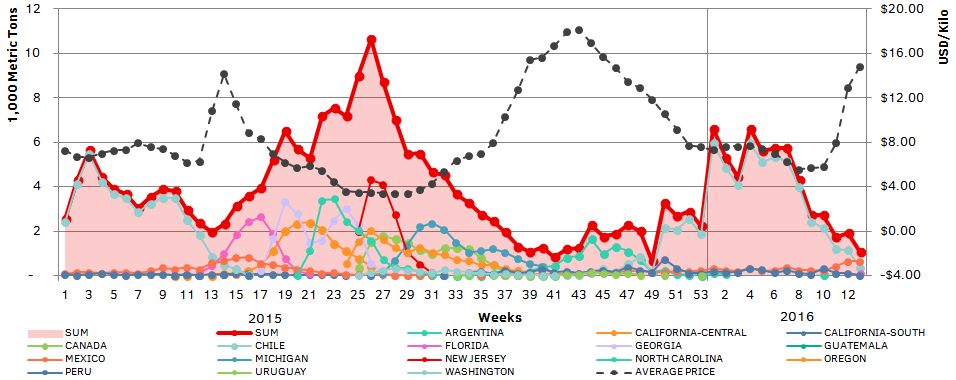

The first step is to estimate the volumes the market needs to keep prices stable. This is done by considering volume movements based on the market price, which is adjusted to a price of US$9.26/kg (average shipping point over the last 10 years reported by the USDA). For the purposes of this study we propose looking at this line as demand, or in other words, more volume is arriving than what is demanded (the red line is above the blue line) when the price falls below US$9.26/kg. This is typical for the United States, and on the other hand if the market is undersupplied the price goes up, which tends to occur between the Chilean and U.S. seasons.

Market supply

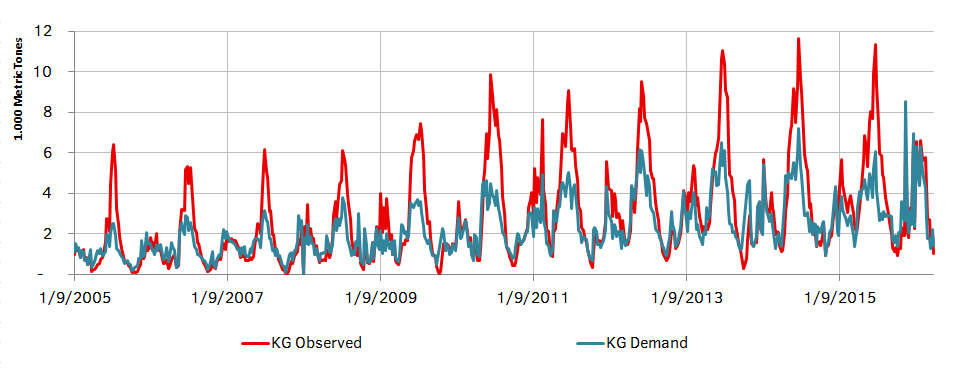

This is where things get interesting. To be able to visualize the evolution of supply shortages over the last decade, we have plotted supply on a three-dimensional matrix, but to be able to see relevant patterns we can also see it in 2D.

In these graphs the green areas and above mean arrival volumes are greater than demand, while the red areas show when the market is in shortage and the price exceeds the aforementioned US$9.26/kg. The height or depth of these highs and lows show by how many kilograms the market was either over- or undersupplied.

In 2005, prices in general were above the historic average with just 67,000MT, with large red valley zones in the graph between the Chilean and U.S. seasons. The difference in price in these periods offered opportunities to growers and they have sought to make the most of it, closing the gap over time. A lot of their efforts have required years of careful study, exploring new production zones and varieties to offer fruit availability to consumers who are willing to pay for it.

Window 1: Chile ends, the U.S. starts

The first window we’ve defined is between the end of the Chilean season and the start of the U.S. deal. This has been the most quickly changing window over the last 10 years; in 2005 it stretched from weeks 8-22 but last year it was drastically reduced to between weeks 13-17.

This evolution has come about thanks to the continued development of Chilean production, which has continued to plant more volumes in the country’s south to provide late season fruit. It is also important to take note of the evolution in the U.S. season, which has been increasingly progressing towards an earlier season with growth out of southern productive states like Florida. On the other hand, we can not leave out Mexico which sends 70% of its volume between weeks 8-21. In 2010, Mexico surpassed the 1,000MT mark in exports to its northern neighbor, growing to 9,000MT in 2014-15.

Window 2: The U.S. and Canada come to an end, South America kicks off

In the second window we observe trends that while similar, are much less dramatic. From what can be observed with northern productive zones of the United States and Canada – the major market suppliers between weeks 28-40 – there has been a growing line of demand, keeping prices very high during the period. Regarding exporters, mainly Argentina and Chile, you can see there has been a lot more of an effort to make the most of the high prices offered in the market.

Until 2011, both Chile and Argentina significantly increased their volumes exported before price falls had a great impact on profitability. The years that followed have been a bit calmer, growing at rates a bit faster than the market but not like what was seen in the first window. Part of the reason why this window has offered higher prices is the cost of production in different growing areas. For phytosanitary reasons, Argentina’s product is exported by airfreight, which adds significant costs that require higher prices for exporters to find profit.

Implications for the future

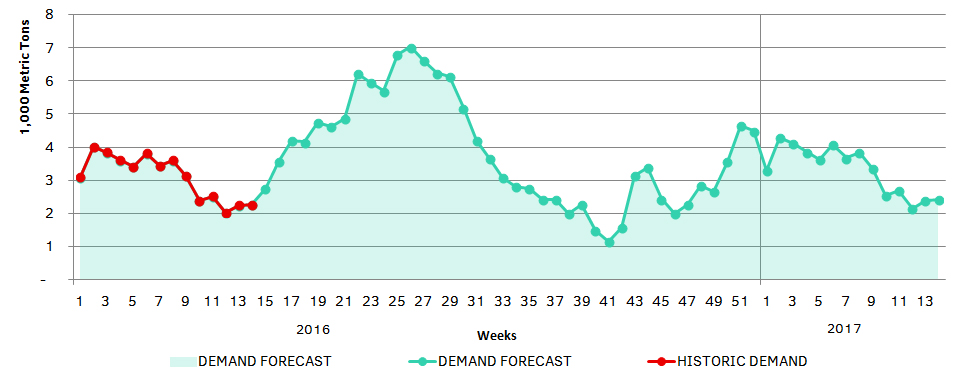

Assuming growth in line with what we have seen in recent years, the volume necessary to keep prices at US$9.26/kg would be approximately 192,000MT over the 52 weeks.

In this graph we use trends observed over the last decade to create a volume forecast of what needs to reach the market to maintain the historical average price of US$9.26/kg. It is interesting to note volume does not surpass 7,000MT per week at the height of the U.S. season, and the lowest point is in week 41 at 1,000MT.

As different origins have different production costs and incentives for exporting to the U.S., it is not expected these volumes will be reached, and nor will there likely be a stable price over the whole season. As they are physically in the market, U.S. growers can benefit from prices that would be unthinkable for the Chilean industry, where the fruit has to meet certain quality standards to be able to make the journey of crossing to the Northern Hemisphere over the course of two or three weeks before reaching the final customer.

However, by nature there will be advances in technology, geographic and botanical exploration, and constant efforts to reduce costs and reach the market when the best prices are offered. A good example of this will be Peru, which mainly competes with Argentina at the start of the Chilean season. Its natural advantage will be in that the fruit can arrive by ship, offering an alternative to Argentina at a lower cost.

05/05/2016

Fresh Fruit Portal